With anything we observe, there is always a context. In the case of Machu Picchu, that context includes the development of cultures in the Andes of South America, the rise of the Inca civilization, and the conflict between Indigenous peoples and Spanish conquerors that played out across much of the Americas. Machu Picchu itself was one of many remarkable Inca construction projects—but one that the Spanish never discovered. For that reason, it remained “lost” to the outside world for centuries, until its reintroduction in 1911.

1. The Inca Empire — Up to 1532

Prehistoric and Early Cultures

Humans likely first reached South America between 12,000 and 18,000 years ago, or perhaps even earlier, traveling rapidly down the coast after crossing from Siberia. The exact dates and routes are still being refined with new discoveries. At the beginning of this period, people were primarily hunter-gatherers, but between 9000-3000 BCE, a transition to early agriculture and sedentary villagesbegan.

Pre-Incas: 3000 BCE – 1470 CE

Thousands of years, geographic isolation (deserts, mountains, rainforest), local adaptations, and cultural innovation led to distinct ethnic and cultural groups in the Andes long before the Incas became prominent. At the beginning of this period, permanent settlements were being built with architecture consisting of pyramids, plazas, and stone and adobe construction. Significant skills development by various ethnic groups were made

in stone carvings, ceramics, textiles, metallurgy (masters of smelting, alloying, casting, and metalworking with gold, silver, copper, tin), stone architecture, agricultural terraces, irrigation, stone paved roads, interlocking stones for building (the original legos?), astronomy, urban and planning, and administration.

Inca Empire

Historically, the Incas were a small ethnic group living in the Cusco valley in the 1

2th–13th centuries. They called themselves the Quechua people, and the same name was given to their language. Quechua is a spoken language only; they did not have a corresponding written language. Spanish missionaries translated the Quechua sounds into Spanish words using Spanish pronunciation. The word “Inca” comes from the Quechua word pronounced as “Inka”, which meansemperor or king of the empire. Over time, the Spanish and later historians extended the term to refer to the entire civilization and even to the people of the empire.

In 1438 a fierce rival ethnic group assaulted Cusco with tens of thousands of warriors (some chroniclers say 40,000). The Inca king Viracocha Inca and his heir, Urco, fled the city, believing the battle was already lost, but one of Viracocha’s younger sons—Cusi Yupanqui—refused to retreat. He rallied loyal forces, and led a surprise and strategic counterattack, using terrain and ambush tactics.

After the victory, Yupanqui gained immense prestige among the nobility and military. He took the throne and renamed himself Pachacuti Inca Yupanqui, meaning “Earth-Shaker”—a reference to the dramatic transformation he was about to initiate. He also promoted the idea that he was the direct descendant of the sun god, Inti, giving him divine authority, too.

Historians agree that with the beginning of the reign of Cusi Yupanqui, the Inca empire started.

Pachacuti is known for his skilled leadership and the following accomplishments:

- Built an empire by expansion of territory through alliances, military conquest, and diplomacy. His son, Topa Inca Yupanqui, continued his expansionist policies, eventually doubling the empire’s size. Expansion continued by his later successors, eventually stretching the empire from southern Columbia in the north to western Argentina and mid-Chile in the south. The population reached 10-12 million people, but only about 100,000 people were of direct Inca ethnicity.

- Organized the empire into a highly centralized bureaucracy of four regions radiating from Cusco. Each region had an appointed governor, and was divided into communities, the basic social, economic, and kinship unit of Andean life — a kind of extended family or clan-based group. A community (or perhaps more than one) had a leader who reported to a governor. All land was claimed as belonging to the state.

- Developed an organized labor “tax” to support state projects (roads, agriculture, military, food production, textile production, metal workers). Commoners, generally males from 15-50, owed about three months of labor per year, more or less, depending on the type of labor.

- Expanded and systematized state-owned storehouses to some 50,000 – 100,000 individual adobe or stone buildings. The storehouses were located along the Inca road system, near administrative centers, in fertile growing areas, and by strategic military centers. They housed food and various supplies used to support armies on military campaigns, workers performing their owed labor, and to feed the population during famines or poor harvests. The storehouses were carefully designed to use ventilation and elevation for food preservation.

- Standardized “Quechua” as the empire’s spoken language.

In addition, Pachacuti instituted a massive building program beginning with the rebuilding of Cusco into a grand imperial capital, with stone palaces, temples, and infrastructure. One reference called Cusco a gated community for nobles. He was the master planner for constructing the following:

- The Temple of the Sun, central to Inca religion, dedicated primarily to Inti, the sun god. The walls were covered in sheets of gold, and there were golden statues, altars, and ceremonial vessels. It was said that life-sized golden llamas and corn plants adorned the site.

- The Sacsayhuamán fortress, a massive stone complex on the mountain about 600 feet above Cusco

- Ollantaytambo as both a royal estate and fortress, shaping its layout and function. His successors maintained and added to it, but the core vision — monumental terraces, strategic importance, royal residence — was his.

- Machu Picchu, a royal estate? a ceremonial center in the mountains? a pilgrimage destination? No one knows for sure. Although lost to the outside world for centuries, it became internationally known in 1913, and received UNESCO World Heritage Site status in 1983.

- The Qhapaq Ñan, a stone-paved Inca road network begun in earlier ages. It grew to over 25,000 miles, unifying the empire. It included suspension bridges made of woven grass (replaced annually), steep stairways, tunnels, and drainage systems all in difficult terrain. The Inca road system was not for the general public—it was a state-controlled network built for the military, resource distribution, rapid communication, and religious ceremonies.

All of ths accomplishments were made without a monetary system, markets, or a conventional written language.

Record Keeping

Record keeping was accomplished by quipus. A quipu, meaning “knot” in Quechua, is an ancient record-keeping device made of knotted strings. The oldest known quipus found by archaeologists date back to around 3,000–4,000 BC. It was a system of visual and tactile communication, used for storing information — like an ancient Andean “spreadsheet” or “database.”

A quipu was made with a main cord with multiple pendant cords hanging from the main cord. Sometimes, subsidiary cords hung from the pendants. Knots were tied in specific patterns and positions with different colors and thicknesses of cord. They were made from cotton or camelid wool (llama/alpaca).

Under Pachacuti, quipus were standardized and expanded empire-wide for:

- Census records

- Tax (labor) records

- Agricultural production

- Military organization

- Possibly history and storytelling, but this remains a mystery.

Túpac Inca Yupanqui, 1471-1493

Pachacuti’s son, Túpac Inca Yupanqui, was remembered as the last great consolidator of Inca power. He mostly continued his father’s territorial expansion plans, enlarging the empire north into present-day Ecuador and south into northern Argentina and Chile. The population is estimated to have reached 10-12 million people, but precise numbers are not available due to the lack of records. Of the total population under the Inca’s control, only 100-200 thousands subjects were ethnically Incas.

Hyuanya Capac, 1493-1527

Túpac’s son and Pachacuti’s grandson, Hyuanya Capac, continued the tradition of expansion but to a lesser degree. He spent most of his time as Inca near the northern pre-Inca settlement of Quito (the present-day capital of Ecuador). Huayna Capac likely died of smallpox or another European disease, introduced before the Spanish physically arrived. New diseases ran rampant through the indigenous populations, traveling much faster than the Spanish who brought them.

The arrival of European diseases in the Andes—especially smallpox, but also measles, influenza, and typhus—caused catastrophic population loss across the Inca Empire, even before the Spanish conquest began in earnest. While exact numbers are impossible to determine, 60-90% (6 – 10 million people) likely died from diseases on the Andean region alone over a 50 – 80 year period. In contrast, a very approximate 150-200 thousand people died because of warfare.

Civil War

As Huayna Capac died from smallpox, so did his designated heir, leaving two other sons, Atahualpa in the north where he had been governing with his father, and Huáscar in Cusco, about 1,250 miles away along the Capac Ñan (Inca road).

Huáscar demanded that Atahualpa submit to his rule, but Atahualpa refused and launched a military campaign, supported by veteran generals from his father’s northern army. A long, bloody war ensued, but Atahualpa won in late 1532 when two of the northern generals defeated Huáscar’s army. Huáscar was captured in November 1532 and his execution, along with family, concubines, unborn children, and supporters was ordered later that month.

The timing could not have been worse for the empire. Loyalties were now divided, and thousands of soldiers died during the civil war. The war devastated Inca infrastructure, agriculture, and leadership; and the Spanish had landed.

2. Francisco Pizarro, Conquistador

In the late 1400s–early 1500s, news of Columbus’s voyage to the new world and the discovered wealth in the Indies reached Europe. It gave poor, mostly illiterate young men with virtually no chance for advancement in life a possible way out. Francisco Pizarro was born illegitimate in 1475 in the “slums” of a small town in the Extremadura region of what is now Spain. The region itself, was a poor, dry, semi-frontier land that bordered Moorish Spain.

Given this description of Extremadura, perhaps it is no surprise that other well known explorers & conquistadors found a way to escape from their dire prospects:

- Vasco Núñez de Balboa — European discoverer of the Pacific Ocean

- Juan Ponce de León — European discoverer of Florida

- Hernado de Soto — explorer of Florida, Georgia, Alabama, & Mississippi, and the first European to see the Mississippi River

- Hernán Cortés — conqueror of the Aztec empire in México (second cousin to Francisco)

Divine Division

1493: Pope Alexander VI, in order to resolve competing colonial claims by Spain and Portugal after the voyages of Christopher Columbus issued a Papal Bull (decree) in 1493. The decree granted Spain exclusive rights to colonize and evangelize newly discovered lands west of a certain line in the Atlantic Ocean (ultimately giving Brazil to Portugal).

1501: Queen Isabella ratified the Pope’s decree as “God’s Will” claiming the population of any discovered lands were her subjects, and therefore had no rights to resist the Pope’s decree. Inhabitants of these lands would be required to convert to Christianity and pay tribute to their Monarch. The effect, and the argument used by future conquerers, was to consider anyone who did not submit to Spanish / Divine authority a rebel, subject to execution. All that had to happen was to inform the native population.

Conquistadors

Conquistadors, contrary to popular understanding, were not professional soldiers working for and paid by the king. They were private citizens and wannabe conquerors who hoped to accumulate stolen wealth from native people and subdue them to live off their labor.

In the early 1500’s, companies were legally formed as private expeditions organized by one or more conquistadors to explore,conquer territory, and claim riches (especially gold, silver, land, and native labor). The structure of such a company included anexperienced conquistador as leader; investors to fund ships, arms, supplies; soldiers/fighters; clerics to legitimize and Christianize the mission; and scribes, notaries, sailors, and interpreters to provide support. All members were promised a share of the plunder — based on their role and rank, and what they brought to the expedition. A soldier would get a share; a soldier with a horse would get a larger share.

Pizarro’s Path to Conquest

Circa 1502: As a way to escape poverty and seek fortune, Francisco Pizarro sailed to the New World “Indies” at age 24 on a ship headed to Hispaniola Island. It is likely that Pizarro served in a military unit used to quell native rebellions, thereby learning how the Spanish dealt with indigenous people.

1510: Rumors of gold and new lands led many, including Pizarro, to move from Hispaniola to a land which would become Panama.There, Vasco Núñez de Balboa was involved in a political fight to become the leader of the first permanent Spanish colony on the America’s mainland. Pizarro’s support of B alboa landed him as one of his loyal lieutenants.

1513: Pizarro was chosen as captain and second in command of one of Balboa’s companies, helping him lead the crossing of the Isthmus of Panama through jungle and mountains. After weeks of hardship, Balboa’s party reached the Pacific Ocean — the first Europeans to do so. Pizarro stood with Balboa at the moment of claiming the Pacific for Spain.

However, there was no gold to be found. On the way back, somewhat irritable, Balboa tortured and executed some native chiefs who told him they knew nothing about where gold may be. It was another lesson Pizarro learned about people skills.

Pizarro gained experience as a leader and explorer, made a reputation among fellow conquistadors, andgave him connections to influential men. These skills and relationships would help him win royal support for future expeditions and organize his conquest of Peru (two decades later).

1519: Hernán Cortés, ten years younger than Pizarro, captured Moctezuma II and kept him captive, thus seizing control of the Aztec empire in what is now Mexico. Cortés’s conquest of the Aztec Empire provided a powerful model and inspiration for Pizarro’s later conquest of the Inca Empire by showing that a small European force could defeat a massive indigenous empire.

1520s: Spanish settlers in Panama were hearing reports of a rich land far to the south where people who wore gold and silver, and towns were built of stone.

1524: Pizarro formed a conquest company with two partners, a financier, and Diego de Almagro, also from Extremadura. When the expedition was manned and supplied, a ship with 80 men and four horses headed south to what is now Columbia. The year-longexpedition faced dense jungles along the Colombian coast, along with swamps and rains, hostile natives, starvation, disease, and constant lack of supplies. Pizarro’s partner, de Almagro, lost an eye in a clash with a native.

No major gold or clear signs of the fabled empire were found, so the expedition was miserable and nearly failed. Still, the expedition gave Pizarro valuable experience with the Pacific coast geography, native peoples, clues about a rich empire farther south, and it laid the groundwork for later, more successful expeditions.

1526-28: On his second voyage, Francisco Pizarro sailed with three ships and approximately 160 men, reaching the northwestern coast of modern-day Peru, just south of the Ecuadorian border. In the Inca coastal city of Tumbes, they encountered friendly inhabitants, though communication was limited to gestures and signs. Despite this, the Spaniards managed to learn of a powerful ruler named Huayna Capac, who resided in the interior. Most strikingly, they saw abundant evidence of gold and silver, confirming rumors of a wealthy Andean empire.

Pizarro kept his ultimate intentions to himself, using the expedition as a reconnaissance trip, but he concluded that he had found his conquest opportunity. He retuned to Panama with two Inca boys gifted to him, who were to be converted to Christianity and taughtSpanish in order to become translators. He also had other Inca gifts to help prove the wealth of a newly discovered civilization.

1528-29: Pizarro, together with his half-brother Hernando, sailed to Spain to petition King Charles I of Spain (also Holy roman Emperor Charles V) for legal authority to conquer the land south of Panama. In July 1529, Queen Isabella, in King Charles name, granted Pizarro a royal charter called the Capitulación de Toledo.

Key provisions:

- Pizarro was granted the right to conquer the land south of Panama, stretching approximately 700 miles south from the Santiago River in present-day Ecuador.

- Pizarro was bestowed the lifetime titles of Governor, Captain General, and Adelantado (military commander and colonial administrator) of the territory once conquered.

- Pizarro and his company were promised a share of the profits (both treasure and land).

- Pizarro had to finance expeditions himself or with partners.

In return:

- Pizarro had to claim all lands for the Crown.

- He was expected to convert the native populations to Catholicism (for both religious reasons and for control of the native population).

- Pizarro was required to send 20% of all gold, silver, and other wealth to the royal treasury.

Notably, his partner, de Almagro, was not included in the charter, ultimately causing serious friction between the two in years to come.

However, for Spain and Pizarro, the charter was probably the most lucrative contract in history!

Before returning to Panama, Pizarro easily recruited new, young conquistadors from his old home region of Extremadura. In addition to Hernando, Francisco also recruited half-brothers Juan, Gonzalo, and Francisco Martín.

1530, January: Pizarro returned to Panama as a royal agent, and he immediately began to organize, staff, and supply his third and final expedition to the south.

1530, December: Three ships and 180 men and horses departed Panama to engage the Incas. (As a comparison, Cortés’s expedition to México had somewhere between 500 and 600 men.) In addition to the horses, those who would be the soldiers and horsemen had steel weapons (swords, lances, knives), steel armor, several early versions of a musket called a harguebus, and as many as four small cannons.

1532, April/May: Pizarro landed at Tumbes again, but this time it lay in ruins, and much of the population had disappeared. He learned of Inca Huayna Capac’s death in 1527, and that a long bloody civil war had broken out between two two sons, Atahualpa in Quito in the north and Huáscar in Cusco in the south. Pizarro discovered that Atahualpa’s generals had won some decisive battlesagainst his brother Huáscar, marking the anticipated end of the war. Atahualpa was reportedly on his way to the Andes city ofCajamarca, to rest there with tens of thousands of troops before advancing on Cusco.

1532, September: With only 168 Spaniards, 62 horses, and weaponry, Pizarro began his journey from Tumbes to Cajamarca to meet Atahualpa. It was a two-month march of 600 miles requiring climbing 9,000 feet up into the Andes. On his way, he continued to collect information about Atahualpa and his troops, and he sent messages to Atahualpa, offering peace and a desire to meet him.

Meanwhile, Atahualpa was informed about the arrival of strange bearded men on the coast by local messengers and scouts. There were reports of “sticks that made thunder and smoke”, large animals that had never been seen before, abuses to natives made by the strange men, and a desire for gold and silver. They were marching toward Cajamarca. Atahualpa was curious and cautious about the strange newcomers. He wanted to know why they were here and what they wanted.

1532, November 15: Pizarro crossed the final mountain pass and saw the nearly empty city of Cajamarca in the valley below. Atahualpa and his army were encamped just outside the town near hot springs. Pizarro and his men saw an endless array of tents, and realized they were outnumbered by estimates of 30,000 to 80,000 soldiers.

Although hiding his intentions thus far and lying about offering peace, the stage was set for Pizarro to replicate Cortés’s success. Pizarro had more horses but about one third the number of men than Cortés did. Although Pizarro appeared confident, the odds seemed overwhelmingly against their survival. Their ability to capture the Inca ruler and hold him hostage were far less than certain.

3. Clash of Cultures

1532, November 15: Pizarro and his company descended the mountain and entered Cajamarca. They housed in buildings across from a single entrance to a huge, walled plaza, while an emissary of 15 horsemen rode to the Inca camp.

Upon finding Atahualpa, the emissary leader read a prepared speech about the supreme pontiff, the Holy Roman emperor, Governor Pizarro, how the local inhabitants disrespected the one true God, and how they can receive and accept the true word, etc, etc.

With a boy interpreter who did not speak formal Quechua very well and who barely understood Spanish, the speech may have had little impact on the Inca emperor. Overall, Atahualpa appeared unimpressed and dismissive, although he agreed to meet Governor Pizarro the next day. He was still curious, and they “certainly were not a threat”.

It was a restless night for the Spaniards trying to find a possible plan to stay alive and capture Atahualpa.

Beginning of the end of the Inca civilization

1532, November 16: Atahualpa arrived unarmed, carried on a litter, with thousands of attendants, expecting diplomacy — not battle.

A Spanish friar, Vicente de Valverde, reportedly handed the Inca emperor a Bible, demanded that Atahualpa accept Christianity and Spanish authority. Assuming he understood the translation, Atahualpa refused, reportedly tossing the Bible to the ground. This was used as a pretext for attack.

Hidden Spanish cavalry launched a sudden strike, mounted on horses with steel swords. At the same time, the small cannons were fired, along with the few harquebuses. The surprise and firepower shocked and scattered the Inca attendants. The horsemen cut down hundreds of panicked nobles in minutes.

Atahualpa was seized alive, while at least a thousand of his men were slaughtered in the chaos. With the divine ruler a captive, his troops were paralyzed for fear that he would be killed. Despite being hugely outnumbered, the Spaniards suffered virtually no losses.

Atahualpa offered a ransom to fill a large room (22’ x 17’ x 8’) where he was being held with gold and silver in exchange for hisfreedom. Pizarro agreed, with no intention of fulfilling his part of the agreement. Atahualpa sent word to his army about bringing treasure as a ransom, and it was slowly brought to Cajamarca over a few months. It was Atahualpa’s hope that the unwelcome visitors would take what they wanted and then leave.

The Incas delivered the largest ransom in history, With just today’s metal prices alone, the ransom is considered to have been worth from 330-400 million in today’s dollars.

1533, July: With the ransom paid, and fearing Atahualpa remained a threat, Pizarro executed him, most likely his intent all along.

Spanish consolidation

1533, August: With reinforcements from Panama and Spain, Pizarro’s force grew to 500 men. The smell of wealth spread quickly throughout central America, and new adventurers were eager to volunteer.

With the recent Inca civil war tearing the empire apart, those who opposed Atahualpa aligned with the Spaniards, hoping to regain control through Spanish support. Manco, a younger brother of Huáscar and Atahualpa, but part of the Cusco faction, threw his support to Pizarro. Many of the non-Inca ethnic people who were forcibly conquered saw the Spaniards as liberators against the Inca elite.

Pizarro was clever to reward new allies with autonomy in exchange for soldiers, reward Inca’s to join his growing army for privileges and loot, and to plan to install Manco as a puppet emperor to maintain control.

With his army and thousands of new native allies, Pizarro left for a 500-600 mile march to Cusco.

1533 November 15: Pizarro entered Cusco with little direct resistance — much of the city had been abandoned or partially burned by retreating Inca forces. The Spaniards installed Manco Inca as a figurehead and began consolidating Spanish control.

- Cusco, the former Inca capital, was transformed into a Spanish colonial city.

- The Spanish demolished or repurposed Inca palaces, temples, and plazas, and built Catholic churches, monasteries, and colonial buildings on top of Inca stone foundations.

- Inca religious practices were banned, and Catholic missionaries worked to convert the local population. Sacred Inca objects (like the mummies of rulers) were destroyed or hidden.

- The Spanish plundered Cusco’s gold and silver, especially from sacred sites. Inca gold and silver treasures were melted down and divided among conquistadors, with the Crown getting their 20%.

- Local Inca elites who cooperated were given privileges; others were displaced or killed.

- Much of Cusco’s cultural heritage was destroyed, stolen, or repurposed for Spanish use.

Two of Francisco’s brothers were left in command of Cusco, Hernando and Gonzalo. Hernando was the senior of the two, and he oversaw the city and dealt with Manco Inca. Hernando was known for being strict, ambitious, and sometimes brutal, especially toward native elites.

1535: After being installed as a puppet ruler in 1533, Manco Inca Yupanqui initially cooperated, hoping to regain his family’s position and restore order.

His situation deteriorated for a number of reasons:

- Hernando reportedly publicly humiliated and imprisoned Manco for a period of time.

- Many Inca noblewomen, including members of the royal family, were abused and were forcibly taken or “appropriated” by Spanish conquistadors as wives or concubines.

- Gonzalo Pizarro is historically noted for having taken Manco Inca’s principal wife, as his own.

- Manco realized he was merely a figurehead with no real power.

1536: Manco escaped Spanish custody early in the year under the pretense of retrieving a sacred statue. Instead, he began organizing a massive resistance.

A thirty-six year death spiral for an empire.

1536, May: Manco returned with tens of thousands of Inca warriors — estimates range from 40,000 to over 100,000. They surrounded Cusco where about 190 Spaniards, including Hernando and Gonzalo Pizarro, were holed up. The siege lasted for about 10 months, and it was one of the most serious threats to Spanish rule in the Americas. Inca forces burned much of Cuzco, destroyed storehouses, and cut off supply lines. Manco’s military strategy was well-organized and nearly successful, but the Spanish held the city with superior weapons and horses, native allies, and nighttime cavalry raids.

1537 early: After the failed siege, Manco fled to Vilcabamba (now called Espíritu Pampa), a remote jungle stronghold. There he established a new Inca State which continued to resist Spanish rule for nearly 36 years. Manco was assassinated in 1544 by Spanish fugitives he had sheltered — a betrayal. His sons, Sayri Túpac, Titu Cusi, and Túpac Amaru — continued the resistance.

1572: Túpac Amaru was captured and executed, ending the last Inca state.

What happened to the Pizarro’s?

1539: After the siege of Cusco, Hernando Pizarro returned to Spain to defend the Pizarro family’s interests in a growing conflict with the family of Francisco’s estranged partner, Diego de Almagro. Hernando brought with him a large quantity of treasure, hoping to win favor with the Spanish Crown, but he was arrested and charged with: misrule in Peru, execution of Diego de Almagro, and illegal enrichment. Hernando was imprisoned for 20 years in Spain — an unusually long sentence for a conquistador — and was finally released around 1559. He died a few years later, wealthy but disgraced.

1539: Gonzalo Pizarro departed Cusco after being appointed governor of Quito by Francisco. He was sent north to consolidate Spanish control over newly conquered areas and expand the empire eastward across the Andes. Over 200 Spaniards, hundreds of indigenous allies, and thousands of animals (including dogs and pigs) began the grueling march over the Andes. The expedition faced horrific terrain, freezing cold, and steep mountain passes.

Many died before reaching the lowlands of the Amazon Basin, but the expedition pushed deeper into dense rainforest with dwindling supplies. Disease, hunger, insect swarms, and hostile environments took a heavy toll, and Gonzalo ultimately had to lead the surviving men back to Quito in total failure. Fewer than a third of the original group returned making it one of the most devastating Spanish expeditions in the New World.

1541, June 26: Francisco Pizarro was assassinated in his Lima palace as a result of a bitter power struggle with the family and supporters of his former partner, Diego de Almagro.

1544-1548: After returning from the failed expedition, Gonzalo revolted against the Spanish Crown’s new laws intended to protect indigenous people. He was captured and executed in Cusco by beheading, ending his rebellion Per Spanish chroniclers, his head was publicly displayed in Lima; his decapitated body was interred in Cusco under the altar of the church of La Merced.

4. Machu Picchu, Revealed

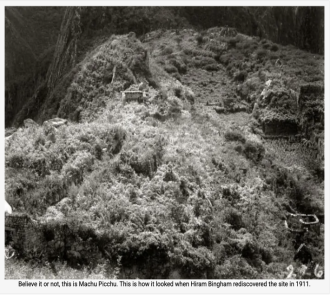

Perhaps at the end of the Inca civil war, or a least no later than the late 1500’s, Machu Picchu was abandoned and left to the elements. Even by Inca standards, the site was remote, and with the collapse of the state, there would have been little reason or ability to maintain such a secluded site, especially if its religious or administrative purpose was no longer relevant.

The Spanish never found or even knew about Machu Picchu during their conquest of the Inca Empire, and historians believe this is due to a combination of geographic isolation, and lack of strategic or economic importance. Therefore, it doesn’t appear in the Spanish colonial records, maps, or conquest reports—suggesting that even Inca informants didn’t mention it to the conquistadors.

Fast forward over 400 years: Hiram Bingham, the son and grandson of Hawaiian missionaries, became a Yale professor of Latin American history. It was a time of growing interest in exploration and discovery in the world’s remote regions, and Bingham was eager to be part of it. He was particularly fascinated by pre-Columbian civilizations and the Spanish conquest of South America. His research led him to accounts of a lost Inca city called Vilcabamba—the final refuge of the Inca resistance. Bingham believed that finding this city would bring him prestige and recognition as a modern explorer.

When leading a Yale-Peruvian Scientific Expedition to Peru in 1911, Bingham heard stories of remote Inca ruins from locals, missionaries, and earlier explorers. In Cusco at the time, his team traveled on the recently completed road to a small settlement near what is now Aguas Calientes.

Once there, local farmers and landowners told Bingham about old ruins in the nearby mountains. To indicate where, one of the local farmers pointed to a mountain and said it was “Machu Picchu”, meaning “Old Mountain” in Quechua. The farmer, agreed to guide Bingham to the ruins the next day.

On the morning of the climb, it was raining, and the trail to Machu Picchu was steep, slippery, and overgrown. The climb also required crossing a log bridge over the Urubamba River, which was dangerous and uninviting in bad weather. The other team members did not want to make the difficult, muddy trek in such conditions, but Bingham was undeterred, and made the climb accompanied by the farmer guide and a young local boy. He carried a Kodak camera, most likely a Kodak No. 3A Folding Pocket Kodak, or a similar model.

After several hours of strenuous climbing, on July 24, 1911, they reached the ridge where Bingham discovered the site was inhabited by a few local families farming on the terraces. When the boy showed Bingham around, he saw the stone terraces and structures of Machu Picchu, largely overgrown but remarkably intact.

“Suddenly we found ourselves in the midst of a jungle-covered maze of granite houses! It was like a dream.”

“I was astonished to find that the buildings, although they had been ruined by time, were still standing, and that the finest stonework I had ever seen was right there in front of me.”

- Hiram Bingham, describing his first impressions of Machu Picchu in 1911

Bingham used this camera to take the earliest known photographs of the Machu Picchu ruins. His photos were essential in documenting and publicizing the site once he returned to the U.S. Many of these images appeared in National Geographic’s April 1913 special issue, their first issue dedicated to one subject.

Returning to Peru in 1912 and 1915 with support from Yale University and the National Geographic Society, Bingham conducted excavations and mapping of the site. He unearthed terraces, temples, tombs, and hundreds of artifacts and skeletal remains, which he exported to Yale, leading to later legal disputes with Peru. In 2011, Yale agreed to return thousands of items.

Although later evidence showed that the Machu Picchu site was not the lost city of Vilcabamba, it was “lost” to the outside world for centuries. Hiram Bingham did not discover Machu Picchu in the truest sense of the word, but with the help of National Geographic, he was the first outsider to document it and bring its significance to international attention.