In 42 years of travel, I have been the travel-planner for all our trips except for four: an Alaska small ship cruise & Denali Nat’l Park tour, two rafting trips through the Grand Canyon, and this fabulous, well-organized trip arranged by Tauck travel. It was very refreshing to leave the travel details to others, but for photographers, an organized tour has its disadvantages, too. In particular, there were stops we would have traded for more time at others.

Both Machu Picchu and the Galápagos Islands are UNESCO World Heritage Sites. The designation is prestigious in that it highlights the global importance of a specific location, whether it be cultural, historical, or natural. It also plays a vital role in conservation and preservation efforts. Both Peru and Ecuador have instituted laws that limit the number of visitors at a given time, require visitors to be accompanied by certified guides, along with other strict rules which help protect their respective sites.

Machu Picchu, Peru

On a Saturday morning, the first tour day, our group of 37 gathered in our Lima hotel lobby, already well-briefed by Tauck on our itinerary. We met our tour director, Jonas Gonzalez, who reviewed the day’s logistics and gave each of us audio receivers and earphones for guided tours. Then we boarded two buses bound for Lima’s historic center.

Lima, the capital of Peru, was established by conquistador Francisco Pizarro in 1535. He laid out the Plaza Mayor (main square) that still exists today, and the Plaza was our first stop. The cathedral and nearby churches were begun during his rule, though earthquakes over the centuries led to many being rebuilt or extensively renovated. After visiting the Plaza, we headed to the Larco Museum for lunch and a tour of its remarkable collection of artifacts spanning 5,000 years of Andean civilization. The day ended with a hands-on demonstration of how to make Pisco Sours (Peru’s national drink) and ceviche, a popular seafood dish “cooked” in lime juice.

The next morning, we took an early two-hour flight to Cusco, former capital of the Inca Empire. The term “Inca Empire” is commonly used, but originally the word “Inca” referred only to the title of the ruler. The people of the Cusco Valley identified themselves as Quechua-speaking. Quechua (KETCH-wah) is still spoken in the Andes today and is the third most spoken language in South America.

When the Spanish seized Cusco in 1533, they looted its gold and silver, destroyed sacred artifacts, and banned Inca religious practices. Yet nearly 500 years later, Inca engineering still endures in the city’s foundations. It’s impossible to walk a block in the historic district without seeing modern buildings—including a Marriott hotel—built atop ancient Inca stonework. The Church of Santo Domingo, built atop the original Temple of the Sun (Qoricancha site), was damaged in two major earthquakes, yet the Inca stonework underneath remained intact. The 1950 quake revealed hidden sections of these ancient walls, which are now visible to visitors.

We visited two major Inca sites outside Cusco: Sacsayhuamán, a fortress and ceremonial complex 600 feet above the city, and Ollantaytambo, a massive fortress and royal estate 44 miles away. From Ollantaytambo, we took a train through the steep Urubamba River gorge to the small tourist town of Aguas Calientes, located at the base of Machu Picchu (MAH-chew PEAK-chew). During the ride, the dry Andean scenery transformed into a lush cloud forest.

From Aguas Calientes, we ascended 1,300 feet by bus along a mountain road full of switchbacks to reach Machu Picchu , meaning “Old Peak” in Quechua. The site is officially listed as “Machu Picchu Historical Sanctuary”, but its purpose is not exactly known. Many historians believe it to be a “royal estate” for the Inca (ruler), as it does not have the housing capacity for a city. Also, there is no evidence that it is a fortress.

Photos don’t do it justice, and seeing the sanctuary before me with my own eyes was breathtaking. After a two-hour tour that afternoon and a one-hour tour the next morning, I quickly concluded: not enough time! As a photographer, I think at least two full days at Machu Picchu would suffice. (Perhaps three.)

The rebuilding of Cusco and the construction of Sacsayhuamán and Ollantaytambo began in the mid-1400s, and were mostly complete by around 1500. During the Spanish conquest, Machu Picchu was suddenly abandoned, most likely due to the collapse of the Inca leadership. It remained hidden to “outsiders” for centuries, preserved largely because the Spanish never discovered it.

A common theme for me, considering all the ruins we visited, was the Inca architecture. The type of stonework and its finish is a good indication of the importance of a building.

- The lowest form of stone architecture used by the Incas is often considered to be “fieldstone” or “rubble masonry.” Uncut stones, perhaps using mortar or mud, were used to build agricultural terraces or rural buildings where the emphasis was on functionality.

- Polygonal masonry is noted for stones of all sizes, precisely cut with multiple angles and sides. The fit was exact, leaving no room to insert even a razor blade between stones.

- Ashlar masonry used finely dressed, rectangular stones that are also cut to fit together in a precise manner. This technique was often used in important buildings such as religious structures.

On the first Thursday of our tour, after spending 3½ days in the Andes, we spent an entire day flying back to Lima and then on to Guayaquil, Ecuador, our gateway to the Galápagos Islands. Since it took most of the day to get there, we spent the night in a hotel and took the earliest possible flight the next morning.

Galápagos Islands, Ecuador

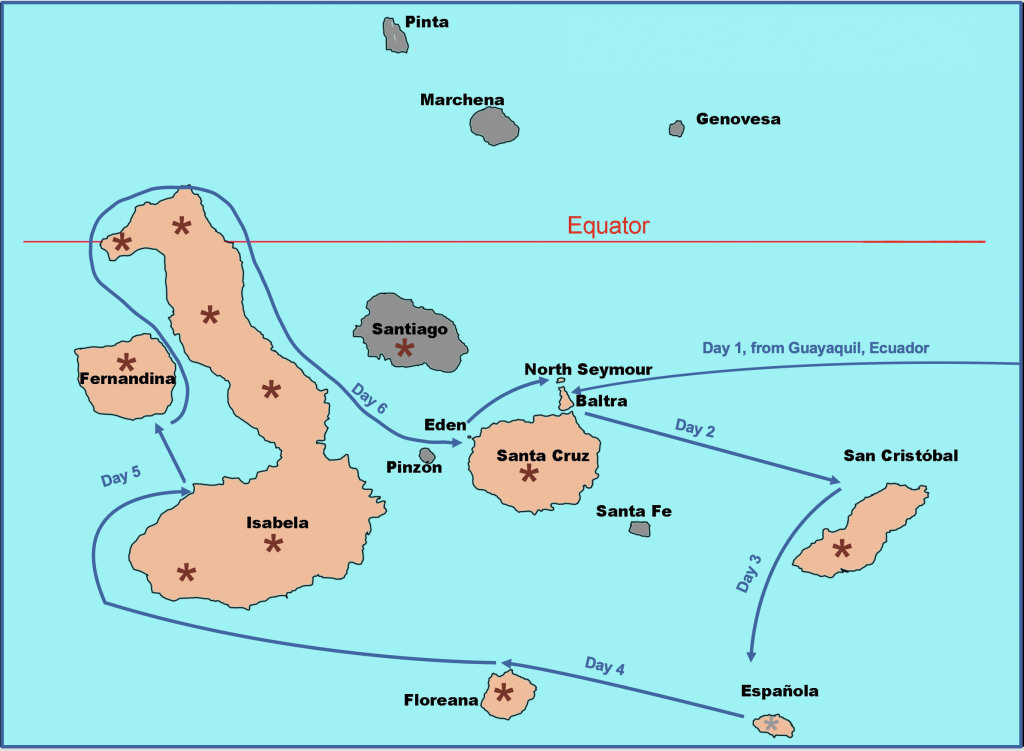

We landed at the Baltra Island airport in the Galápagos. A brief ferry ride brought us to Santa Cruz Island, while our luggage was transferred to our live-aboard expedition ship and home for six nights, the Isabela II. An “expedition” ship is licensed by the Galápagos National Park Directorate. They are designed for visitors to become the explorers of the unique islands and marine environments of the Galápagos archipelago according to the strict laws governing the National Park.

The map shows six of the thirteen islands we visited in addition to the smaller Eden Islet and North Seymour Island. Most of the major islands have one extinct volcano except for Isabella which has one extinct and five volcanoes that have erupted since 1954, the most recent one in 2022. Fernandina has an active volcano that last erupted in March 2024!

Underneath Fernandina is a “hot spot” in the Earth’s crust that is a volcano-creator. As the tectonic plate on which the islands sit slowly drifts to the southeast, a new island may appear to the west of Fernandina in a million years (plus or minus). Meanwhile, the volcano cones on the easternmost islands will continue to erode. The volcano cone on Española is completely eroded.

The lure of the Galápagos is wildlife! Most of the animals are unfazed by the proximity of humans, so it is possible to observe them up close (keeping at least six feet away).

Because of the islands’ isolation and harsh conditions, many animals have had to evolve over millions of years to survive. Acquired traits have been significant enough for some animals to become different species than their original ancestors that first settled in the islands. These species are called “endemic” because they are not found anywhere else in the world.

Choosing a favorite animal is tough, but the non-endemic Boobies were high on our list. Their name likely comes from the Spanish “bobo”, meaning “fool” or “clown”. Though excellent fliers and divers, they appear clumsy and vacant‑eyed on land. We saw three species—Blue‑footed, Red‑footed, and Nazca—but the Blue‑footed Boobies were everywhere, and their elaborate mating dances were especially entertaining. The bluer the feet, the healthier the male—something the females apparently know well. One pair had taken up residence on a narrow trail, and they refused to move. We had to step off the marked trail and into the grass to pass.

Two standout endemic species demonstrate extraordinary evolutionary adaptation: the Galápagos Marine Iguana and the Galápagos Flightless Cormorant. Darwin described the Marine Iguana as “a hideous‑looking creature, of a dirty black colour, stupid, and sluggish in its movements.” Yet he was fascinated by its evolved ability to swim, dive, and feed on underwater algae—something no other iguana in the world does.

What makes a bird lose the ability to fly? The key factor is the lack of predators. The endemic Galápagos Flightless Cormorant, with its stubby wings, comical appearance, and webbed feet, evolved to dive rather than fly. It is twice the size and heavier than most cormorants, and has no feather oil, which helps it dive deeper and longer to catch larger fish.

We also saw two non‑endemic Frigatebirds, which are agile in the air but cannot dive or even land on water to feed. If their feathers get wet, they may not be able to take off, and could likely drown. To eat, they steal food midair from other seabirds, a behavior known as kleptoparasitism.

Other endemic species we saw included the rare Galápagos Waved Albatross and Galápagos Hawk, the Galápagos Penguin (the only penguin that lives at the equator), and the Galápagos Lava Heron, Lava Lizard, Mockingbird, Sally Lightfoot Crab, and Dove.

Viewing wildlife could not have been easier. Each day, we explored the coastlines and protected bays on panga boats. In addition there were daily hikes on the islands and snorkeling for those comfortable to do so. As an alternative, there was a glass bottom boat for viewing underwater life, and kayaking was also available. With two activities in the morning and two in the afternoon, there were abundant opportunities to view wildlife.

Each day was a sensory overload—not just from the wildlife, but also from the dramatic volcanic landscapes and snorkeling views (though sadly, no there are no underwater photos to share). Add in the delicious food, happy hour cocktails, comfortable accommodations, and educational lectures, and the experience was first class. Our Tauck tour director and our local guides were attentive, helpful, knowledgable, fun to be with, and they were an important reason our trip was very successful.

Six days and nights in the Galápagos passed quickly. Every morning when we woke up, we were at a new island, each unique and offering new wildlife species. Unlike the first part of the trip, there was no downtime due to travel, only a brief ride on a panga. As long-time divers, our only regret was not being able to capture the underwater life in photos: baby sharks, sea turtles, sea lions, schools of fish, and more.

Although different, both Machu Picchu and the Galapagos Islands never failed to enchant. Yes, they are magical places and are deserving a spot on bucket lists.

Photography

Much of my photography over the years has been directed to landscapes. Following the norms, I consistently used a tripod to ensure no “camera shake” in order to create the sharpest photographs. In addition, with a tripod, I could search for and lock-in the best composition I liked. I enjoyed using an ultra-wide lens so that I could get a good focus from near to infinity. It may be obvious that this approach took time — more time than raising my camera and taking a picture.

In this trip, I learned in my research that Machu Picchu does not allow tripods unless you get a permit. Other restrictions for touring Machu Picchu include “closely” following a guide (same with the Galápagos) and not retracing your steps to get a photo you missed. The trails are one-way, and tourists are not permitted to go against the traffic, which can be considerable. For both locations, tripods are just not practical.

I have never been enthralled with bird photography, but the lure of several feathered species in the Galápagos twisted my arm and I tried my best to prepare for birds-in-flight photography. This involved several specific camera settings for which I had little experience. To get good at capturing BIF, the pros emphasized the need for practice, practice, practice. Well, the trip would be my practice using continuous focus, burst mode, high shutter speeds compensated by auto-ISO, and using either zone focus or bird subject selection. I used a 70-300 mm zoom lens plus a 1.4 teleconverter on my Fuji X-T5 (cropped sensor) resulting in a maximum focal length of 630 mm equivalent to a full-frame sensor. This was a fairly good reach, but then trying to maximize the subject size of a flying bird in my viewfinder was another challenge.

I had a lot of misses even with stationary birds, probably par for the course, but I think I got some decent shots as well. You be the judge while viewing the Galápagos photo gallery.